When I discovered that the frontman of my favorite band (Radiohead) was composing the soundtrack for one of my favorite films, I knew Suspiria (2018) would be entirely different from its 1977 predecessor. Thom Yorke’s haunting, melancholic compositions redefined the film’s tonal aesthetic, steering it away from the supernatural horror of Argento’s classic and into a realm of psychological dread and introspection. Suspiria (2018) unraveled itself as something wholly distinct from the original, and nowhere was this transformation more potent than in its soundtrack. Thom Yorke’s ghostly, melancholic compositions seeped into the film’s bones, dissolving the feverish supernatural horror of Argento’s vision and replacing it with something slower and more sorrowful—a descent into psychological unrest and existential dread.

Jonathan Gray argues that paratexts create systems of orientations that influence how a viewer engages with a text. In the case of Suspiria (2018), Yorke’s haunting soundtrack guides the audience to approach the narrative through a lens of internal, existential horror rather than external supernatural threats. This “realm of the ‘between’” utilizes external and contextual experiences to facilitate the audience’s consumption and understanding of the film (Gray 48).

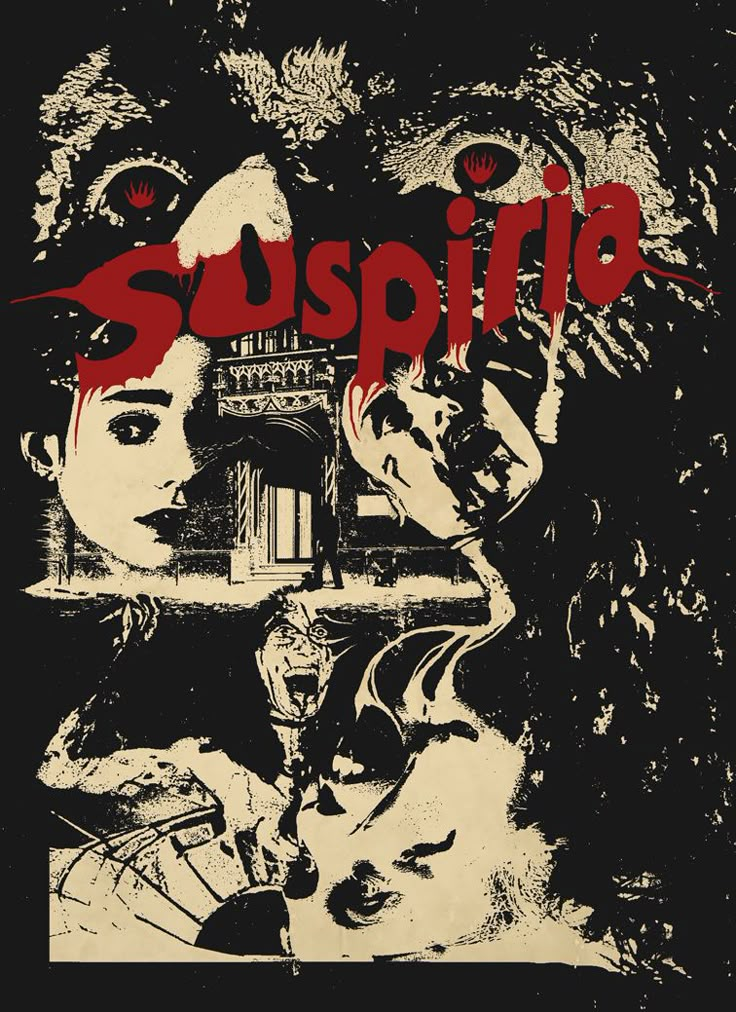

This essay will perform an analysis of Thom Yorke’s Suspiria (Music for the Luca Guadagnino Film) to argue that Suspiria (2018) deliberately distances itself from Argento’s Suspiria (1977) by disrupting one of its most recognizable paratexts: its soundtrack. In stripping away Goblin’s dissonant, progressive rock score—integral to the original film’s identity—and replacing it with Yorke’s atmospheric, melancholic compositions, Suspiria (2018) perceptively reorients itself from supernatural gothic horror to psychological art horror.

Music plays a crucial role in Suspiria as an extension of the film’s core themes: dance, violence, ritual, and transformation. In both versions, the soundtrack is inseparable from the movement of the dancers, dictating the rhythm of their bodies and the occult forces at play. Goblin’s score in the 1977 film is aggressive and dissonant, mirroring the erratic, almost violent choreography that feels possessed by an unseen force. In comparison, Thom Yorke’s 2018 soundtrack is more fluid and hypnotic, aligning with the film’s reimagining of dance as a spiritual and psychological battleground rather than mere performance. Tracks like Suspirium emphasize the ritualistic nature of movement, their rhythmic repetition reflecting the power dynamics and bodily sacrifice within the coven (Yorke, “Suspirium”). This shift in musical tone transforms the film’s horror—rather than something external and chaotic, it becomes something internal, a force that consumes from within, blurring the line between art, magic, and destruction. The music itself becomes an incantation, an auditory spell that pulses through the film, reinforcing its psychological terror.

Goblin’s Suspiria (1977) score works in tandem with Argento’s heightened visuals, contributing to Suspiria’s status as an audiovisual assault on the senses. The blending of progressive rock with horror creates a sense of disorientation and unease, making the viewer feel as though they are trapped in a waking nightmare. This chaotic soundscape is typically characterized by layered instrumentation, sudden shifts in tempo, discordant synth lines, and eerie choral chants characterize this sonic experience.

Thom Yorke’s Suspiria (Music for the Luca Guadagnino Film) disrupts the tonal aesthetic of the original with a more melancholic and introspective soundtrack, emphasizing psychological deterioration rather than supernatural horror. Suspirium, with its soft piano and airy vocals, introduces a sense of grief and isolation that aligns with Guadagnino’s thematic concerns—trauma, oppression, and the loss of control. Lyrics in songs like Unmade reflect irreversible loss: “There’s still no faces / Won’t grow back again / Broken pieces / Unmade” (York, “Suspirium”, “Unmade”). The titles of the tracks, such as The Inevitable Pull, The Universe is Indifferent, A Soft Hand Across Your Face, and Voiceless Terror, further reinforce the film’s existential and psychological weight (York, Suspiria).

Each soundtracks alters the viewer’s perception of horror: Goblin’s Witch is an unrelenting sonic assault—layered shrieking vocals, erratic percussion, and distorted synths create a sense of inescapable dread. The track blurs the line between sound and diegetic fear, effectively transcending from simply accompanying horror to purely embodying horror (Goblin, “Witch”). In contrast, Yorke’s Has Ended takes a more subdued, hypnotic approach, using a steady drumbeat and droning instrumentation to evoke an underlying sense of ethereal decay rather than immediate terror (Yorke, “Has Ended”). Where Goblin’s compositions heighten the film’s nightmarish unreality, Yorke’s music turns inward, forcing the audience to experience fear as something creeping, inevitable, and deeply embedded within the characters themselves.

A key moment of narrative and musical divergence between the two films is Suzy Bannion’s first dance at the academy. In the original, Suzy is visibly weak and disoriented. Despite her insistence that she is too ill to continue, Miss Tanner pressures her to push through the routine. As Goblin’s ominous Suspiria – Celeste and Bells looms in the background, Suzy’s vision blurs, the room tilts, and she ultimately collapses, reinforcing the supernatural forces subtly manipulating her body (Argento, 28:28; Goblin, “Suspiria – Celeste and Bells”). However, in Suspiria (2018), Suzy’s first major dance sequence is an entirely different experience. She exudes confidence and determination, despite Madame Blanc cautioning her on the difficulty of the routine. As she dances, the music shifts—Yorke’s Olga’s Destruction–Volk Tape replaces Goblin’s frenzied sound with a rhythmic pulse, heightening the trance-like atmosphere (Yorke, “Olga’s Destruction– Volk Tape”). With each movement, Suzy unknowingly binds herself to the coven’s dark magic, her dance physically tethered to Olga’s gruesome destruction in a mirrored chamber (Guadagnino, 34:15). This epitomizes how music reshapes the film’s horror: in the 1977 version, the soundtrack amplifies Suzy’s victimization, whereas in the 2018 version, it portrays her underlying power and the unsettling symbiosis between dance and witchcraft.

Yorke’s association with Radiohead adds an intertextual layer to Suspiria (2018), influencing how fans interpret the score and, by extension, the film itself. Radiohead’s discography, particularly albums like Ok Computer, Amnesiac, and A Moon Shaped Pool, is known for its exploration of paranoia, alienation, and existential unease (Radiohead). Songs such as Burn the Witch, Creep, and We Suck Young Blood (Radiohead) engage with themes of witchcraft, dread, and psychological torment, aligning with the sinister, internalized horror present in Suspiria (2018). Yorke’s established sonic signature—characterized by detached agony, melancholic minimalism, and existential unease—provides an in-media-res paratextual cue that shapes audience reception: rather than expecting a bombastic horror soundtrack, viewers familiar with Yorke’s work anticipate a sonic experience that immerses them in the characters’ psyches rather than external supernatural threats.

Ultimately, removing Goblin’s score was a bold decision that came with inherent risks. Goblin’s music is deeply intertwined with Suspiria’s legacy, and its absence risked alienating longtime fans of Argento’s film. Without its distinctive auditory signature, Suspiria (2018) could have been perceived as detached from its source material or lacking in visceral energy. However, this decision ultimately paid off by reinforcing Suspiria (2018) as a standalone work with its own artistic identity. Rather than relying on nostalgia, Guadagnino’s film used Yorke’s score to create a new sonic framework that deepened its psychological and thematic resonance. In doing so, it redefined the film’s horror as an intimate, lingering presence—one that unravels the psyche rather than simply assaults the senses.

Works Cited

Argento, Dario. Suspiria. 20th Century Fox International Classics, 1977. Goblin. Suspiria: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. Cinevox, 1977.

Gray, Jonathan. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. E-book, New York: New York University Press, 2010.

Guadagnino, Luca. Suspiria. Amazon MGM Studios, 2018. Radiohead. Amnesiac. XL Recordings, 2001.

Radiohead. A Moon Shaped Pool. XL Recordings, 2016. Radiohead. Kid A. XL Recordings, 2000.

Radiohead. OK Computer. XL Recordings, 1997.

Yorke, Thom. Suspiria (Music for the Luca Guadagnino Film). XL Recordings, 2018.

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.