American Horror Story: A Cult Classic?

Since its debut in 2011, American Horror Story (AHS) has cultivated a reputation for shock, transgression, and genre-bending experimentation. With its self-aware engagement with horror tropes, intertextual homages to cult classics, and fiercely devoted fanbase, AHS exhibits many characteristics traditionally associated with cult cinema. Cult films are often defined by their subversive content, rejection of mainstream conventions, their aesthetic and narrative “badness”, and intense fan engagement, qualities that AHS not only embraces but amplifies within the realm of serialized television. This article argues that AHS functions as a modern cult classic by pushing the boundaries of horror through its transgressive narratives, self-conscious play with genre conventions, and ability to foster an obsessive fan culture. By blurring the line between mainstream success and cult appeal, AHS redefines what it means to be “cult” in contemporary television.

Shock, Subversion, and Transgression

AHS consistently seeks to shock its audience through excessive gore, taboo-breaking perversions, and supernatural horror. Each season reinvents itself through a new theme and narrative style, incorporating everything from slasher horror (1984) to supernatural melodrama (Coven) and psychological terror (Asylum). The blending multiple genres of horror creates a unique viewing experience that keeps the audience on edge and challenges their expectations.

Asylum (Season 2) alone features a disturbing array of controversial and shocking content, including a possessed nun raping a priest, alien abduction, graphic bodily disfiguration due to Nazi experimentation, conversion therapy, and a serial killer with maternal rejection issues who performs unsettling acts, including explicit scenes of sucking milk from his victims before dismembering them. One of the most harrowing storylines follows Lana Winters (Sarah Paulson), a journalist investigating Briarcliff Manor, who is committed after being accused of perversion due to her homosexuality. Inside the asylum, she endures intense conversion therapy and electroshock treatment, only to be “rescued” by psychiatrist Dr. Oliver Thredson (Zachary Quinto)—who is soon revealed to be the infamous serial killer Bloody Face. Held captive, Lana is repeatedly assaulted and impregnated by Thredson before managing to escape, only to get into a car accident that lands her back at Briarcliff. With no one believing her claims about Thredson’s true identity, her suffering continues. In the present time, her abandoned child learns his family history and grows up to become the new Bloody Face. This cyclical nature of trauma and violence underscores the show’s unrelenting approach to psychological and bodily horror, reinforcing how past horrors persist in new forms (Murphy, 2012).

The role of gore and shock in AHS extends beyond mere sensationalism; rather, it serves to subvert conventional horror expectations and amplify the emotional and psychological stakes of the narrative. The violence in Asylum critiques institutionalized power structures and social injustices, highlighting the intersection of personal and societal horrors. The conversion therapy scene (S:2, E:9) portrays the dehumanizing practices forced upon queer individuals under the guise of “treatment,” using horror as a means to critique the power structures that perpetuate such injustices. Similarly, Coven (Season 3) examines racism and historical atrocities through the character of Delphine LaLaurie (Kathy Bates), a New Orleans socialite from the 1830s notorious for torturing and enslaving Black people. Resurrected in the modern era, LaLaurie is forced to become a personal slave to Queenie (Gabourey Sidibe), the only Black witch at Robichaux Academy (S:3, E:3). This reversal of power dynamics humorously underscores the show’s engagement with historical horrors and their lingering effects (Murphy, 2014).

This subversive approach permeates the show’s engagement with contemporary politics. Cult (Season 7) directly confronts the socio-political anxieties surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election, using the rise of extremist cult leader Kai Anderson (Evan Peters) as an allegory for political radicalization and mass hysteria. The season blurs the line between fiction and reality, incorporating real political footage and events to heighten its unsettling realism. If the image of Donald Trump appearing in the show’s opening sequence isn’t jarring enough, the season’s exploration of mass fear—through motifs such as trypophobia (fear of small holes), coulrophobia (fear of clowns), and hemophobia (fear of blood)—deepens its psychological impact (Murphy, 2017).

Cult exposes the insidious nature of fear as a political tool, illustrating how horror can transcend fiction to reflect real-world anxieties. The season incorporates real political footage and events, making AHS one of the few mainstream horror series to explicitly engage in direct political commentary within its diegesis. Through this, the show demonstrates how horror can be weaponized as a reflection of societal fears, reinforcing its status as a modern cult classic. By engaging with historical trauma, institutionalized oppression, and contemporary political unrest, the show transforms horror into a vehicle for social commentary. In doing so, it not only entertains but also provokes, challenging audiences to confront the darkness lurking beneath the surface of both fiction and reality. However, the constant barrage of transgressive imagery can also alienate some viewers, raising the question of whether the show’s commitment to shock always serves a deeper purpose or veers into mere exploitation.

Aesthetics: Meta-Horror, Camp and the Art of Deliberate “Badness”

AHS is defined not only by its thematic boldness but also by its distinct aesthetic approach, which merges meta-horror, camp, and deliberate stylistic “badness.” The series frequently plays with genre conventions, self-referential storytelling, and exaggerated performances to both celebrate and critique horror traditions.

Roanoke (Season 6) stands out within the AHS franchise as one of its most experimental and self-referential series. By blending documentary-style reenactments with found-footage horror and reality television, the season constructs a layered critique of media, storytelling, and audience complicity in consuming horror. Roanoke’s defining feature is its dual-structured narrative. The first half, presented as My Roanoke Nightmare, mimics true-crime reenactments, where real-life individuals recount their experiences, performed by actors. This format plays on the sensationalism of modern media, highlighting how storytelling distorts and repackages trauma for entertainment. The second half, Return to Roanoke: Three Days in Hell, deconstructs this further by bringing both the real people and their actor counterparts into the haunted house under the guise of a reality-TV sequel (Murphy, 2016). This shift exposes the artificiality of horror storytelling while making the violence disturbingly real for both the characters and the audience. Additionally, Roanoke critiques the modern entertainment industry’s fascination with trauma, exposing how reality television and reenactments turn real suffering into spectacle for mass consumption while at the same time engaging in those very tropes.

Roanoke’s self-awareness makes it one of the most conceptually ambitious seasons of AHS. Its meta-horror approach not only deconstructs how horror stories are told but also forces the audience to question their role in consuming violent narratives. By blurring the lines between fiction and reality, Roanoke reminds us that horror is not just about ghosts and gore but also about the way we construct, exploit, and relive fear through media.

Beyond its meta-horror tendencies, AHS revels in camp, incorporating self-aware humor and exaggerated performances. The surreal, over-the-top characterizations, such as that of Hazel Evers, the devoted yet gleefully homicidal laundress of serial killer James Patrick March in Hotel, recall earlier cult classics that blended horror with humor (Murphy, 2015). This tonal dissonance heightens the absurdity of the horror elements, making AHS a unique example of narrative subversion where moments of dread are frequently undercut by humor.

Additionally, AHS embraces erratic filming techniques, fast cuts, and unconventional cinematography, particularly through found-footage aesthetics that echo low-budget, cult horror films. Despite its high production value, the series purposefully incorporates elements of “bad” filmmaking—such as shaky camera work and exaggerated lighting—to create a raw, unsettling experience. Roanoke (Season 6) employs handheld camerawork and night-vision footage to heighten its documentary-style horror, while Asylum (Season 2) uses extreme Dutch angles and jarring, rapid cuts to reflect the psychological fragmentation of its characters. Murder House (Season 1) relies on distorted fisheye lenses and quick zooms to create a voyeuristic, claustrophobic effect, and Cult (Season 7) utilizes whip pans, extreme close-ups, and tilted frames to visually replicate the paranoia and hysteria that define its exploration of mass psychosis. This calculated embrace of visual chaos mirrors cult films’ tendency to lean into DIY aesthetics, paying homage to horror’s roots in exploitation cinema while making stylistic imperfection an artistic choice. In doing so, AHS turns the aesthetics of low-budget horror into part of its signature visual language, blending high production with deliberately rough edges to unsettle and provoke its audience.

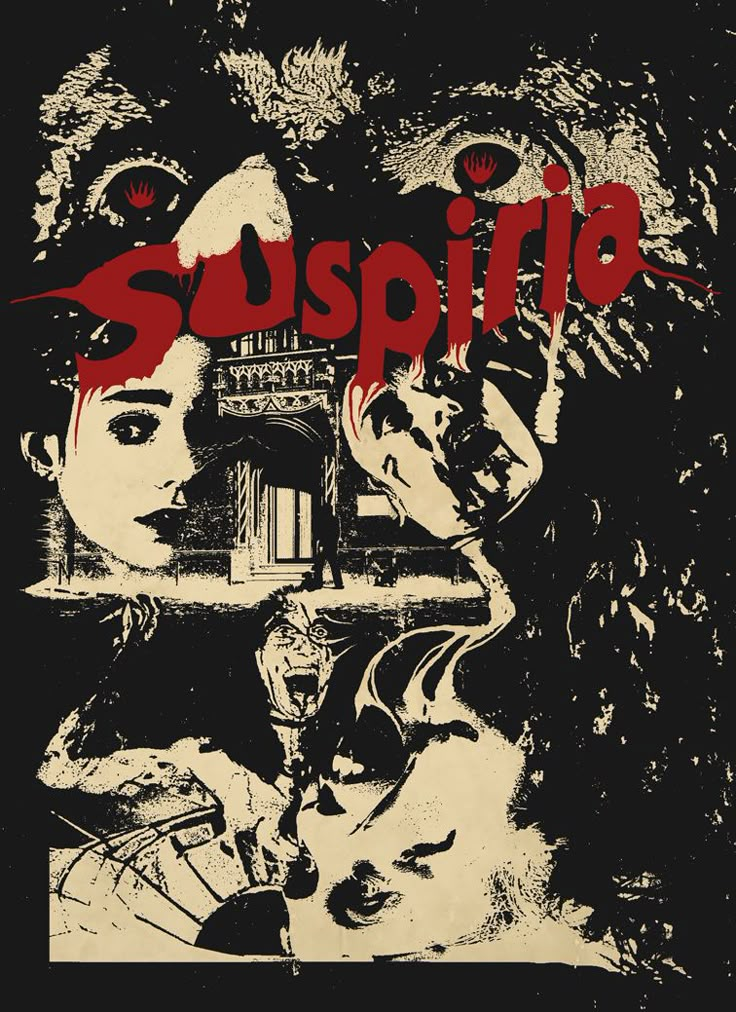

Intertextuality, Exploitation, and the Cult Film Legacy

AHS positions itself in direct conversation with films historically relevant to cult cinema. Freak Show (Season 4) is directly inspired by Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), Hotel (Season 3) draws parallels to The Shining (1980), and Coven (Season 3) aesthetically lends on The Blair Witch Project (1999). AHS doesn’t reworks these references into its own unique brand of horror; for instance, Hotel (Season 5) references real-life figures like Jeffrey Dahmer, Aileen Wuornos, and John Wayne Gacy, inserting them as ghosts invited to the haunted Hotel Cortez for Devils Night, or Halloween (S:5, E:4). It also briefly features a fictional Anne Frank as a patient at Briarcliff Manor in Asylum (Season 2).

AHS thus builds an intertextual web that appeals to horror aficionados by offering layers of recognition, rewarding viewers with a knowledge of the genre’s history and conventions. By referencing cult classics, AHS cultivates a shared understanding between itself and its audience, invoking a sense of community among those familiar with the archetypes of horror cinema.

These reimaginings can be both effective and problematic. The blending of real and fictional horrors in Hotel is a compelling method of deepening the terror, as the audience is forced to confront the terrifying reality of real-world killers alongside supernatural ones. It also portrays the true reality of their everlasting legacy as real monsters, their ghosts evoking a sense of unease that transcends fictive bounds; however, the use of real criminals as characters risks trivializing their actual crimes, walking a fine line between shock value and exploitation.

Moreover, much like earlier cult films, AHS frequently casts high-profile celebrities for shock value and increased appeal. The use of stars such as Stevie Nicks in Coven (Season 3), Lady Gaga in Hotel (Season 5), and Kim Kardashian in Delicate (Season 11) creates a spectacle that draws attention and generates buzz. This taps into the cult of celebrity, where the public’s fascination with these figures enhances the show’s impact and reinforces its transgressive appeal—consider, for instance, Lady Gaga’s role as a sultry, bloodthirsty vampire or Kim Kardashian’s bizarre transformation into a pregnant monstrous spider. This strategy mirrors earlier cult films that often cast controversial or unconventional actors to provoke or challenge audience expectations.

The “cult” nature of AHS is also evident in its constant reinvention. Each season offers a new theme which keeps audiences engaged and fosters a sense of community among those who share in the collective viewing experience. Apocalypse (Season 8) further solidifies AHS’s status as a modern cult classic by weaving together previous seasons into a sprawling, interconnected narrative (Murphy, 2018). This crossover links the previous seasons in a sprawling interconnected timeline rewarding long-time fans with deep lore, character revivals, and intertextual references. By doing so, Apocalypse transforms AHS into a self-referential universe, mirroring the way cult films build mythologies that demand audience investment and rewatchability. This narrative interconnectivity is a hallmark of cult storytelling, where obscure references, hidden connections, and continuity deepens the experience for devoted viewers. This mirrors the way cult films build mythologies that demand audience investment and rewatchability, ensuring that AHS remains a serialized horror phenomenon with a fiercely dedicated fanbase.

Reception and Fan Culture

Historically, films that go on to be included in the cult canon often receive a negative or lukewarm reception upon their initial release due to their provocative or transgressive content, which can alienate mainstream audiences. However, AHS has defied this pattern, cultivating a massive and devoted fan-base while continuing to push boundaries and explore controversial themes. This passionate following thrives on social media, where fans dissect episodes, create elaborate theories, and produce fan art, memes, and video essays analyzing the show’s intricate timeline. Entire websites and YouTube channels are dedicated to unraveling its interconnected seasons, much like how cult horror franchises such as Twin Peaks and The Rocky Horror Picture Show have inspired obsessive fan engagement.

Beyond online spaces, AHS has cemented its influence in real-world fan culture. Every Halloween, cTate Langdon from Murder House and the witches from Coven become staple costume choices, reinforcing the show’s place in pop culture. Fan conventions and themed events frequently feature AHS-inspired panels, cosplay, and escape-room experiences, similar to the immersive fan cultures surrounding horror franchises like The Evil Dead or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. This level of involvement reflects the participatory nature of cult media, where audiences actively shape and reinterpret the material long after its initial release.

Conclusion

In an era where cult films are continually rediscovered and redefined, American Horror Story thrives by embracing excess, transgression, and intertextuality. Rather than merely fitting into the horror genre, American Horror Story warps and redefines it, embracing extremes that repel as much as they entice. Its willingness to indulge in the grotesque, the absurd, and the deeply personal cements its place in television history. In doing so, it doesn’t merely depict horror—it reshapes it, one unsettling season at a time, leaving behind a spectacle that refuses to be forgotten.

Works Cited

American Horror Story Complete Seasons 1-8. FX Network, 2011.

American Horror Story. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/AmericanHorrorStory/.

McKiney, Hannah. “The FULL American Horror Story Timeline.” YouTube. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCe6y7yMnm0.

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.