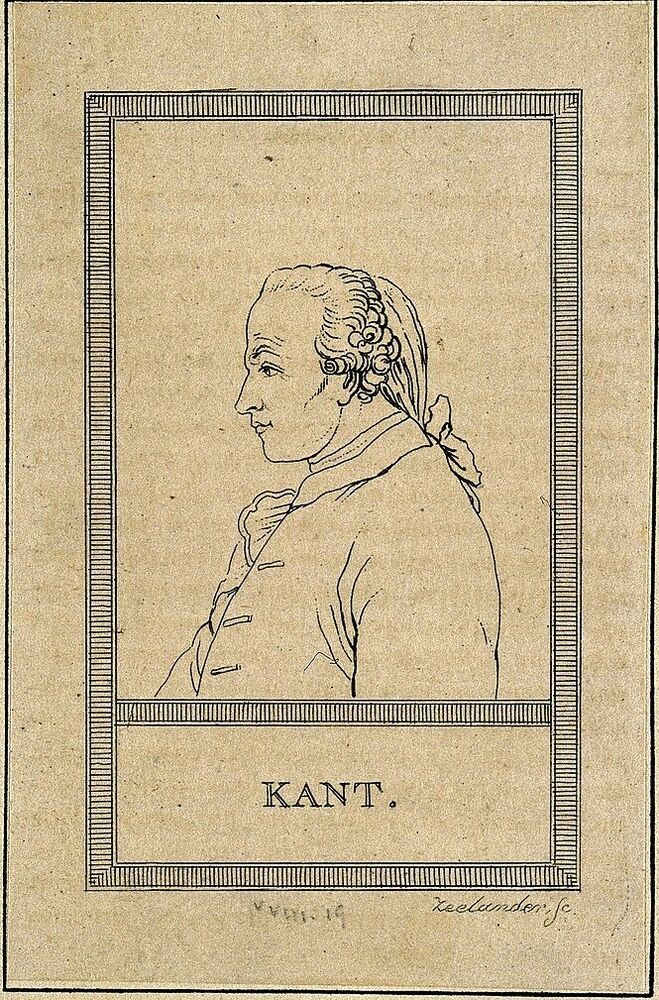

Hume’s empirical skepticism about causal inference contrasts Du Châtelet’s rationalist support for the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR). Analyzing their arguments offers insights into the empirical versus rationalist understanding of causality and induction—the process of inferring the unknown from the known. Hume’s framework, rooted in skepticism and empiricism, challenges the rational basis for causal inference, while Du Châtelet’s rationalism and adherence to Newtonian physics posits the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR) as an epistemological solution to Hume’s skepticism. This essay seeks to evaluate Hume’s skepticism of causality in the context to Du Châtelet’s PSR. It seeks to explore the empirical versus rationalist understanding of causality as well as their epistemological implications on our understanding of observation and inference in the study of causality.

Skepticism and empiricism are central to Hume’s views on induction as he argues that our understanding of causality is not derived from reason but rather from custom and experience. According to Hume, witnessing repeated associations or patterns between events leads to an expectation of it being repeated. Causality is simply custom—the habitual assumption of a repetitive pattern—and, therefore, lacks justification as it is not the product of a logical deduction. He says, “[I]n all reasonings from experience [hence, in all inductive reasonings], there is a step taken by the mind, which is not supported by any argument or process of the understanding” (Hume, first Enquiry, 5.2). This is due to the fact that the very nature of inferring the unknown goes against empiricist principles of valuing sensory a priori experience—since the unknown cannot be observed or experienced, Hume contends that it cannot be known.

This is particularly informed by his Uniformity Principle (UP) which posits the assumption that the future is conformable to the past (E 4.19). According to Hume, this principle lacks a rational basis—no causal inference is warranted a priori as the very nature of something being unobservable necessitates that it cannot be experienced directly. Instead, our understanding of causality is formed on the basis of custom and experience, which is informed by the UP—the assumption that the future mimics the past. Since this principle is not warranted by reason, but rather habitual associations between events, he consequently concludes that inference to the unobserved is ultimately not warranted by reason (Hume, E 4.5-5.2). This challenges the notion of inferring the known based on known patterns, suggesting that such inferences are not warranted by reason, especially regarding unobserved phenomena.

Émilie Du Châtelet poses an epistemological problem to the implications of Hume’s framework. She argues that denying causality would ultimately undermine the certainty of all knowledge. The very concept of identity and universal truths would become untenable, as everything would be subject to perpetual change thrust into the realm of the unknown. As an epistemological solution, Du Châtelet posits the PSR asserting that nothing occurs without a rational explanation. She states “If we tried to deny this great principle [sc., PSR], we would fall into strange contradictions. For as soon as one accepts that something may happen without sufficient reason, one cannot be sure of anything, for example, that a thing is the same as it was a moment before, since this thing could change at any moment into another of a different kind; thus truths, for us, would only exist for an instant…” (Du Châtelet, Foundations, p.721). She indicates the larger implications of denying causality and in doing so, brings forth the rationalist epistemic problem with Hume’s framework.

The PSR ultimately suggests that every genuine possibility (and actuality) is a genuine possibility (Du Châtelet, Foundations, p.742). Its implications include that no two things are indiscernible, there’s no such thing as absolute space, and there are no extended substances (Cottrell, Lecture 13). Du Châtelet’s defense consists of two main arguments discussing the implications of denying PSR: the knowledge of the unobserved and the preservation of identity. Firstly, she contends that if the PSR is false, knowledge of the unobserved becomes untenable, which contradicts our empirical observations. Secondly, she suggests that denying the PSR denies personal identity and the self, which is inherently rooted in causality (Du Châtelet, Foundations, p.721). This principle posits a foundational rationality to the universe, whereby every event or existence must have a cause or reason. Du Châtelet’s argument implies that a rational structure underpins our observations and inferences about the world. This fits her framework which necessitates a metaphysical justification of Newtonian physics, particularly regarding gravity.

Du Châtelet’s defense of the PSR extends to the Uniformity Principle, suggesting that if the PSR holds true, then the course of nature does not change arbitrarily for no reason. Given that we have a priori evidence that nature doesn’t change without reason, one may rationally assume that there will not be a change in the course of nature. Therefore, Du Châtelet asserts that the unobserved future will resemble the observed past—a key tenet of the Uniformity Principle—is grounded in rational thought. This argument rests on the premise that there is a rational basis for the uniformity of nature, as there is no reason for nature to deviate from its established course without cause.

Assessing both positions, it becomes evident Hume’s caution against overextending causal inference challenges unchecked rationalism, while Du Châtelet’s PSR offers a compelling argument for the inherent rationality and order of the universe. However, it is essential to acknowledge that Du Châtelet’s PSR addresses a fundamental aspect of human inquiry—the quest for reasons and explanations. While Hume rightly critiques the potential overreach of causal inference beyond empirical observation, Du Châtelet’s framework provides a necessary philosophical foundation for scientific investigation and metaphysical speculation.

Ultimately, Du Châtelet’s rationalist perspective, anchored in the PSR offers a more compelling framework for understanding causality compared to Hume’s empiricism. Her argumentation provides a coherent and rational basis for causal inference, asserting that every event or existence must have a cause or reason. By positing the PSR, Du Châtelet emphasizes the importance of rational explanations for phenomena, thereby ensuring the coherence and predictability of the universe. Moreover, her defense of the PSR highlights the epistemological implications of denying causality, particularly regarding the knowledge of the unobserved and the preservation of identity. By acknowledging the necessity of causal explanations and the rational structure underlying our observations, Du Châtelet’s perspective aligns with the principles of Newtonian physics and offers a foundation for interpreting the natural world. Hume’s skepticism, in contrast, leaves causality on shaky epistemological grounds whereas Du Châtelet’s rationalist approach provides a more satisfactory account of the fundamental principles governing our understanding of reality.

Hume might argue that Du Châtelet assumes a level of determinism that may not be warranted by empirical evidence. Moreover, he may contend that her reliance on the PSR overlooks the limitations of human understanding and the complexities of causality as observed through experience. Additionally, he might assert that Du Châtelet’s emphasis on rational explanations does not fully address the fundamental problem of induction, namely, the justification for extrapolating from observed regularities to unobserved phenomena. The lack of a rational basis for such extrapolation undermines the certainty of causal inference, regardless of the appeal to rational principles. However, Du Châtelet may counter that Hume’s skepticism underestimates the capacity of reason to discern patterns and derive causal relationships beyond mere habit and experience. Du Châtelet would likely assert that her framework ultimately provides a stronger foundation for understanding causality as it accounts for both empirical evidence and the rational structure of the universe. Ultimately, empirical evidence must guide our understanding of causality, but within a framework that acknowledges the rational order of the universe.

Works Cited

Cottrell, Jonny. 2024. “Lecture 13.pptx”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto, Toronto

Cottrell, Jonny. 2024. “Lecture 14.pptx”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto, Toronto Cottrell, Jonny. 2024. “Lecture 16.pptx”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto, Toronto Cottrell, Jonny. 2024. “Lecture 17.pptx”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto, Toronto Hume, David “First Enquiry Sections 4-8 Feb 1”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto

Du Châtelet, Émilie “First Enquiry Sections 4-8 Feb 1”, PHL210Y1, University of Toronto

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.