Brontë’s Jane Eyre is a text deeply rooted in colonial attitudes and Victorian norms of social hierarchy. Through his novel, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Jean Rhys transformatively engages in a retelling of the narrative through the reconstruction of Bertha Mason into the humanized version of Antoinette. By doing so, it inherently positions Antoinette in opposition to Jane Eyre as a means to evaluate their divergent yet interconnected narratives and the disparities of their lived experiences—particularly, due to the intersectionality of gender and race in the Colonial context. This essay explores the profound parallels and contrasts between these female narrators to evaluate the gendered and racial complexities that permeate their stories. By examining how Rhys reshapes aspects of Brontë’s narrative, we delve into the heart of postcolonial discourse, unraveling the layers of social hierarchy in both novels.

To begin with, postcolonial literature often brings attention to the methods by which language is employed as a weapon of social violence. This is well demonstrated in Jane Eyre where characters like Mrs. Reed use derogatory language to demean and belittle Jane as a means of reinforcing hierarchy. The novel also portrays how language is used to perpetuate injustice through the silencing of victims and the stripping of their personal narratives. Antoinette is often silenced by English characters—the most notable being Rochester—who consider her language and accent inferior. The enforced use of English not only robs Antoinette of her native language but also erases her cultural heritage, contributing to their alienation and loss of self. Later, Bertha, being confined and silenced in the attic, is stripped of her voice and language, symbolizing the violence enacted upon her through linguistic oppression. This portrays how language, when used to reinforce social hierarchies and marginalized individuals, can be just as destructive as physical violence.

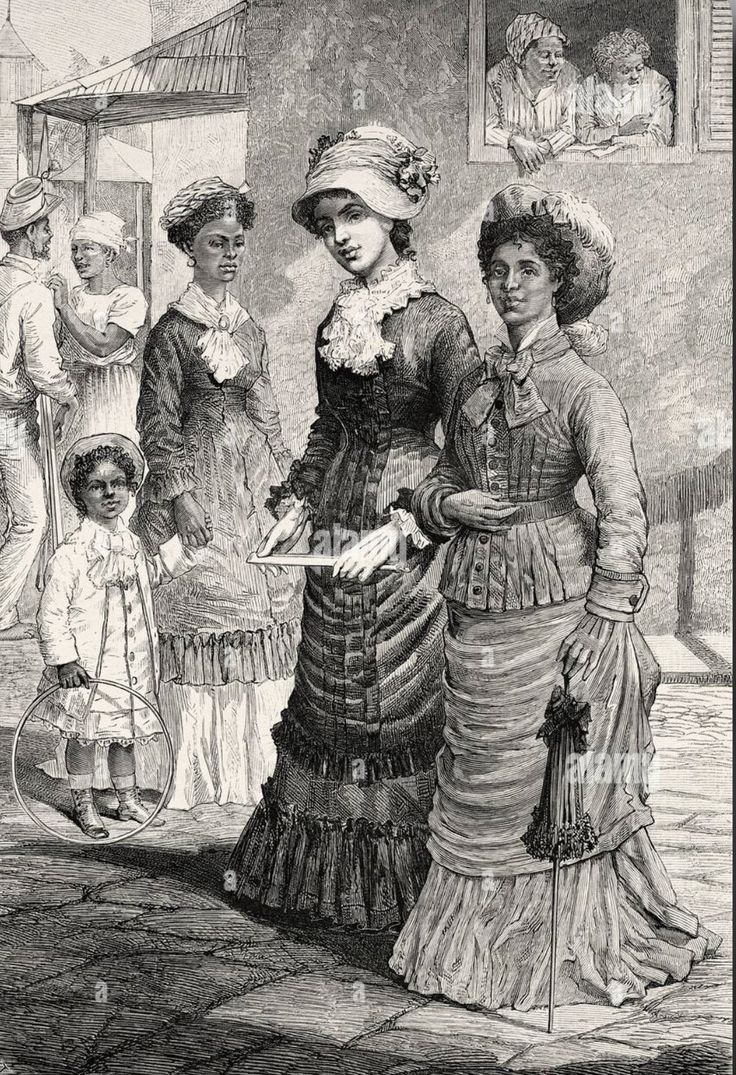

Both narrators experience an intense sense of alienation and display signs of defiance—Jane due to her upbringing as an orphan, and Antoinette due to the racial disparity between her European lineage and her Creole heritage. In her pursuit for belonging, Jane undergoes personal and intellectual growth which further fuels her refusal to adhere to Victorian gender norms of subservience. Jane’s defiance results in her transcending some level of institutional hierarchy. Contrarily, Antoinette struggles to navigate a more intricate intersection of gender and race, woven together in the fabric of colonial gender expectations. Consequently, her defiance against societal expectations becomes entangled with racialized oppression which forces her into stricter confines, accumulating in her total lack of control. This is symbolized through the attic which not only acts as a symbol for her physical confinement, but also the confines of society and her own mind. It underscores the oppression, and powerlessness faced by Antoinette during the loss of her sanity—and consecutively, the loss of her identity. This intersectionality serves as a powerful critique of the intertwined systems of racism and patriarchy, highlighting how racial biases exacerbate gender inequalities.

Both texts portray the overarching themes of beauty, female conflict, and jealousy. Jane is repetitively described to be conventionally average-looking as compared to Antoinette’s striking beauty. However, this beauty is neither understood nor appreciated as it is inherently intertwined with her race. This is evident in Jane Eyre where Rochester compares Bertha to a wolf, himself as a shepherd caring for a lamb that is Jane Eyre. This not only dehumanizes both women but also repeats a pattern wherein Antoinette is repeatedly referred to in a derogatory animalistic manner. Furthermore, in Wide Sargasso Sea, Antoinette’s conflict with Amélie over Rochester’s infidelity serves as a means to display the nuanced complexity of her emotions such as rage, jealousy, and fear. She enacts her emotional distress through drinking and confrontation; however, the intensity of her emotions are deeply misconstrued as symptoms of insanity by Rochester. One may assert that this is due to his limited understanding of emotion within the sphere of a “proper society” that implicates everyone within their established gender and racial norms. By deeming her as insane, Rochester portrays his lack of understanding regarding the depth of feminine emotion and the possibility of culturally varying conceptions of emotions. Antoinette’s emotional response directly juxtaposes Jane’s more ‘rational’ and ‘proper’ response to discovering that Rochester was engaged—by leaving him. This highlights colonial gendered expectations of feminine behavior, particularly, on acceptability of feminine defiance wherein one form of defiance is considered resilient whereas the other is deemed as insanity.

The portrayal of sanity, or insanity, is inherently linked with the narrative structures of the texts. Jane Eyre follows the traditional Bildungsroman chronological structure. The narrative is divided according to symbolic locations in Jane’s life and ends with her happily married to Rochester. On the other hand, Wide Sargasso Sea de-establishes normative rhetorical and temporal principles in accordance with Antoinette’s descent into madness. Her role as a narrator is undermined as she is unable to perform the chronological retelling of the story (de Villiers, 2018). This is further symbolized by her ‘losing’ the narrative to Rochester, as she loses her identity to him as well. She becomes a character in what was initially her own story, symbolizing how her identity has been taken away. Her narrative takes on an associative form rather than a linear one, directed by her fears. This exacerbates her feeling of disconnection, especially considering her sanity is directly linked to her inability to remember or recount her story. The attic is the physical embodiment of the constraints put upon the configuration of her mind wherein she is no longer in control of the narrative and her only solace is the possibility of remembrance. This is why, by the end of the novel, her narrative disposition is fragmented and all she says is “I must remember”.

Works Cited

BBC. (n.d.). Use of structure in Jane Eyre – form, structure and language – OCR – GCSE English literature revision – OCR – BBC Bitesize. BBC News.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zcjm39q/revision/3#:~:text=It%20includes%2038%20chapters

%20in,her%20happiness%20and%20her%20struggles.

Jane and Antoinette. (n.d.). https://victorianweb.org/neovictorian/rhys/farley.html

Mambrol, N. (2020, August 4). Analysis of Jean Rhys’s novel wide Sargasso Sea. Literary Theory and Criticism. https://literariness.org/2019/05/29/analysis-of-jean-rhyss-novel-wide-sargasso-sea/

Simões, B., Dr. (2023, September 18). Week 02 Jane Eyre [PowerPoint Slides].

Simões, B., Dr. (2023, September 25). Week 03 Wide Sargasso Sea [PowerPoint Slides].

Villiers , S. de. (n.d.). Remembering the Future: The Temporal Relationship between Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/69106/DeVilliers_Remembering_2018.pdf

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.