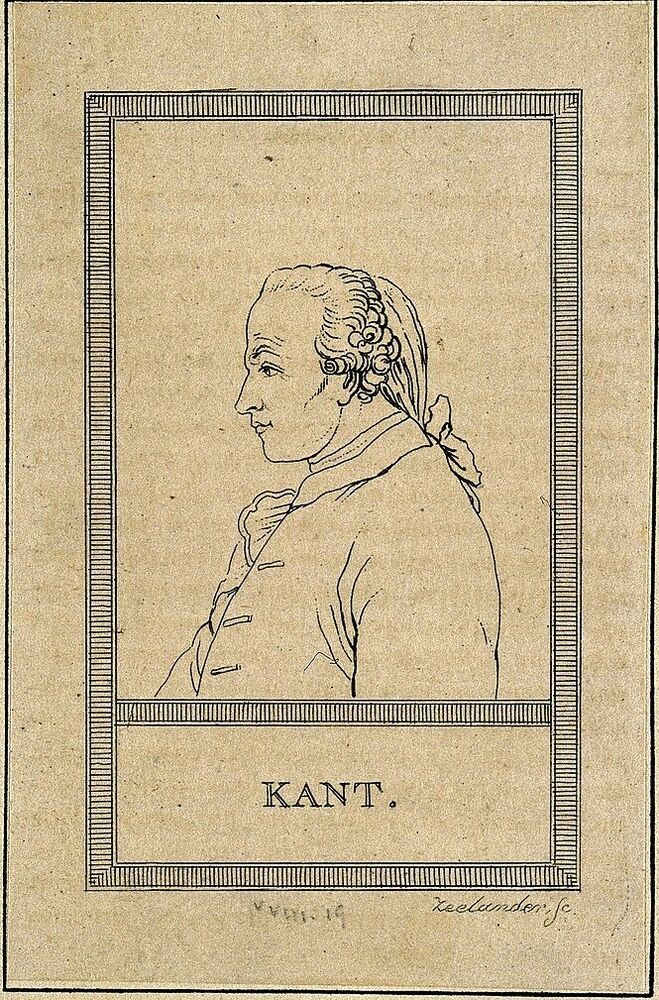

According to Kant, truth is a property of judgments where the representation within the judgment corresponds with its object in the world. As he states (A58/B82), a judgment is true when the way an object is represented in thought matches the object as it is in the world. However, this correspondence is not a direct reflection of external reality but is mediated by the mind’s faculties, which structure all possible experience. Truth, therefore, is not just a matter of subjective agreement; it is conditioned by the faculties of the mind that enable us to perceive and represent objects, grounding the possibility of objective knowledge. This understanding of truth establishes the groundwork for Kant’s distinction between synthetic and analytic judgments, and for how synthetic a priori judgments can serve as the grounds for synthetic a posteriori judgments.

Synthetic a posteriori judgments, such as “The apple is red,” derive their truth from empirical observation. However, these judgments presuppose the operation of the mind’s categories—the pure concepts of the understanding that structure all experience. Categories like causality, substance, and unity are not learned through experience but are the conditions under which experience itself is possible. For instance, when observing an apple falling from a tree, the category of causality must be presupposed to make sense of the event. Without these categories, we could not represent objects as causally related, as having substance, or as coherent within the framework of experience. This means that the truth of synthetic a posteriori judgments is dependent on the mind’s ability to organize sensory data into coherent representations through the categories. Categories like causality, substance, and unity are not learned through experience but are the conditions under which experience itself is possible.

Kant’s claim at A148/B188 that synthetic a priori judgments “contain in themselves the grounds of other judgments” refers to the foundational role these judgments play in making experience intelligible. Synthetic a priori judgments, such as “Every event has a cause,” are not derived from experience but are necessary conditions for it. These judgments are synthetic because they extend our knowledge by connecting concepts not inherently linked (the concept of “cause” is not contained in the concept of “event”), and they are a priori because they are universally and necessarily true. The truth of these judgments is grounded in the mind’s a priori structures, which govern how sensory data must be organized for the world to be experienced as intelligible. By providing the necessary framework for interpreting experience, synthetic a priori judgments establish the conditions under which empirical knowledge is possible.

This dependence on synthetic a priori judgments explains why synthetic a posteriori judgments presuppose the mind’s representation of objects via the categories. The mind applies the categories of the understanding to the sensory manifold, organizing raw data into meaningful representations. For example, the judgment “The apple fell from the tree” relies on the category of causality to interpret the sensory observation of the apple’s motion. Without synthetic a priori principles like “Every event has a cause,” which articulate the structure of causality, such empirical observations would remain disconnected and unintelligible. As Kant explains at A237/B296, the truth of judgments is conditioned by the way the mind structures representations, which ensures that empirical judgments are coherent and meaningful. Synthetic a priori principles thus serve as the universal and necessary scaffolding for all synthetic a posteriori knowledge.

The Copernican Revolution provides the foundation to understanding how the truth of synthetic a priori judgments grounds the truth of synthetic a posteriori judgments. Instead of assuming that knowledge must conform to the external world, Kant argues that the external world conforms to the mind’s a priori structures. This shift, inspired by Copernicus’ profound shift in astronomy—stating that the sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe—allows him to explain how the conditions for possible experience are imposed by the mind, rather than derived from the external world. Synthetic a priori judgments, like “Every event has a cause,” are not contingent on experience but are necessary for organizing experience. They ground synthetic a posteriori judgments by making empirical observation intelligible within a causally and spatially structured framework. The principle “Every event has a cause” ensures that we can recognize the connection between the breaking of a branch and the falling of an apple as a causal event, rather than as a disconnected sequence of sensory impressions.

By grounding the truth of synthetic a posteriori judgments in the a priori conditions of experience, Kant’s Copernican Revolution shifts the basis of truth from a mere correspondence with external objects to a deeper correspondence with the mind’s structures that make perception and understanding possible. This reveals that synthetic a priori judgments provide the necessary conditions for all empirical knowledge by ensuring that sensory data is processed in a coherent and intelligible way. Consequently, synthetic a priori judgments do not simply guide experience but contain within themselves the grounds for the truth of all other judgments, enabling the mind to organize the external world into meaningful, structured representations. This understanding establishes that the mind’s active role in structuring experience is fundamental to the possibility of truth, thereby situating synthetic a priori judgments at the foundation of Kant’s epistemology.

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.