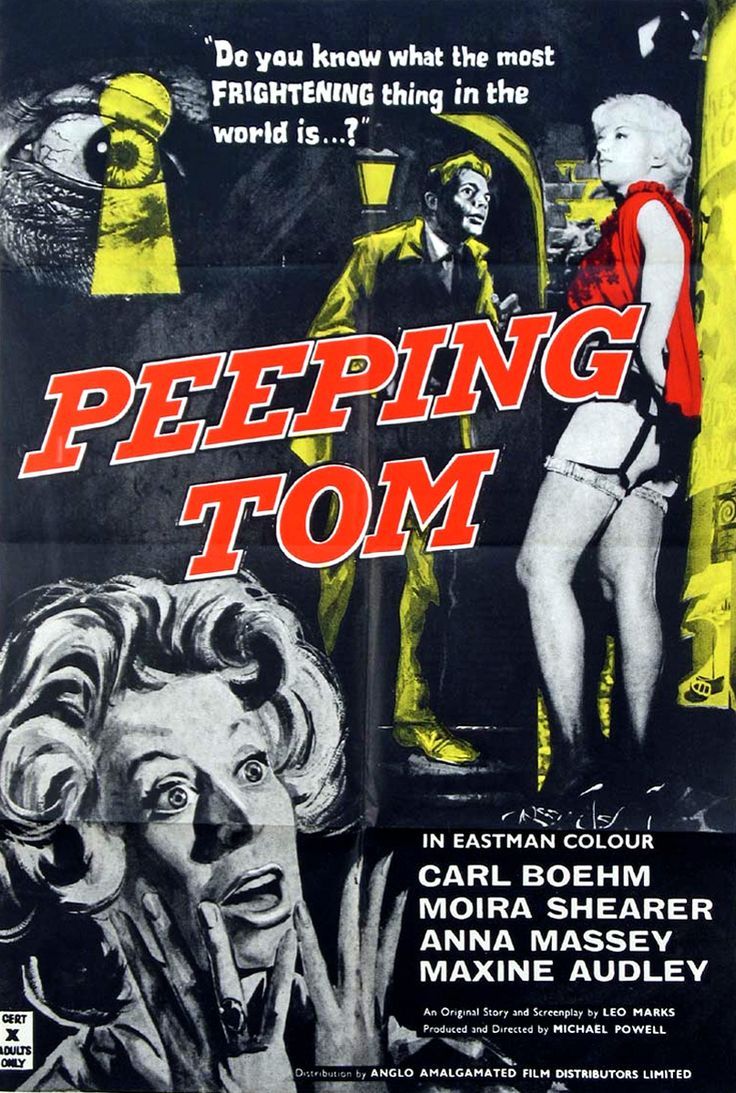

Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) is now widely considered one of the most exceptional horror movies ever made, lauded for its innovative use of subjective camera techniques and psychoanalytic themes. However, this stands in stark contrast to its initial reception, which evoked much outrage—to the extent that Powell himself asserted that it contributed to the collapse of his career at the time (Mulvey). The opposing viewpoints between its reception and now raise questions regarding the cause of the divergence in opinion. This essay seeks to explore the factors that caused this divergence in reception, in 1960 versus in the succeeding decades. I aim to conduct an in-depth close-reading analysis of sections in the film to argue that Powell’s artistic decisions—particularly, cinematic techniques and metaphors that force the audience into complicity—play a fundamental role in the outrage towards the film. To achieve this, the essay will primarily refer to the following primary sources: “Peeping Tom: A Second Look” by William Johnson, “A Very Tender Film, a Very Nice One’: Michael Powells Peeping Tom” by Elliot Stein, and “Peeping Tom” by Laura Mulvey. By examining the film’s historical context and closely analyzing its key scenes, this essay aims to elucidate the lasting appeal of Peeping Tom as a classic film in the horror genre while simultaneously evaluating the controversy surrounding its initial reception.

Peeping Tom’s initial reviews faced severe condemnation from critics. As noted by Elliot Stein, critics like Nina Hibbins in The Daily Worker went as far as to say “[Peeping Tom] wallows in the diseased urges of a homicidal pervert (…) it uses phoney cinema artifice and heavy orchestral music to whip up a debased atmosphere (…) From its lumbering, mildly salacious beginning to its appallingly masochistic and depraved climax, it is wholly evil.” As evident from this quote, the initial negative reception of Peeping Tom can be attributed to various factors—the most evident being the plot which follows Mark Lewis (Karlheinz Böhm), a cameraman who murders women while filming their reactions with a hidden camera. Mark’s obsession with capturing fear on film stems from his traumatic childhood wherein his father conducted ‘experiments’ on him, subjecting him to fear-inducing scenarios to document his reaction. Mark soon gets involved with Helen (Anna Massey), and as his mental state deteriorates, he begins to see her as a potential victim which leads to the climactic point. The film’s narrative links dark themes such as sadism, voyeurism, sexuality, and violence while simultaneously using its cinematic techniques to blur the line between observer and observed. When taking into consideration the initial reception of Peeping Tom, it is essential to note that British film viewers at the time weren’t accustomed to seeing such displays of violence and sexuality on screen— particularly, given that the target audience involved teenagers and young adults. This is further supported by evidence from Laura Mulvey’s article wherein she asserts “Entrenched in the traditions of English realism, these early critics saw an immoral film set in real life whose ironic comment on the mechanics of film spectatorship and identification confused them as viewers,” (Mulvey). Furthermore, the film’s release date, which coincided with the highly publicized trial of the Moors Murderers in the UK, only added to the already heightened sensitivity towards such topics. As a result, many critics and viewers found the film morally objectionable, leading to a widespread condemnation of the movie and its director.

However, it is now notable that the initially perceived factors such as the film’s disturbing plot, explicit themes, and timing of release do not fully explain the extent of criticism against Peeping Tom. This is evident when considering that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), which also featured similar violent themes, was released only a few months after Peeping Tom and yet, was a commercial success. In his essay, “Peeping Tom: A Second Look,” William Johnson draws a direct comparison between the two films, asserting that there must have been other additional elements that contributed to the divergent reception of the two films. He elaborates by asserting that these other factors were related to Powell’s artistic choices, which were perceived as more controversial and subversive compared to Hitchcock’s conventional approach (Johnson). Powell’s use of subjective camera techniques and the self-reflexive portrayal of the protagonist’s complicity with the audience was innovative and daring, leading to a deeper engagement with the audience but also drawing criticism from those who found the film morally objectionable. Moreover, one may assert that the very title of the film, “Peeping Tom”, preconditions the audience to expect explicit content. Despite being informed of the sadistic and voyeuristic themes, it is still noteworthy that the audience reacted with shock. This prompts one to consider the reasons for such a reaction, in this case, Powell’s artistic decisions. Hence, I assert that it was not the narrative content itself, but rather the manner in which the content was portrayed that led to the film’s extensive criticism in 1960.

Powell deliberately used cinematic techniques that implicate the audience in the protagonist’s voyeuristic behavior. From the film’s opening scenes, sex, and violence are apparent, and the audience is aware of the perverse nature of the protagonist’s actions. Through the use of sexual innuendos and metaphorical imagery, Powell implicates the audience, building a deeper connection between them and the protagonist and blurring the boundaries between them (Johnson). As a result, the audience is forced to confront their own morality, leading to a sense of self- reflexivity and complicity in the film’s events. One of the most significant examples of this is the film’s opening sequence, which sets the tone for the rest of the movie. The scene begins with a close-up shot of a camera lens, immediately drawing attention to the voyeuristic nature of the film. As the camera moves back, the audience sees the protagonist, Mark Lewis, filming a woman through a window. Through the use of subjective camera techniques, the audience is placed in the position of the voyeur, watching as Mark films the woman undressing. This technique creates a sense of complicity between the audience and the protagonist, making the audience question their own morality and involvement in the events onscreen. Powell also uses sound design to implicate the audience. The sound of Mark’s camera and breathing is amplified, adding to the voyeuristic and unsettling nature of the scenes it builds a sense of intimacy. This use of sound design is a recurring theme throughout the film, further implicating the audience in the events onscreen.

Powell’s intentional manipulation of sound is also evident during Helen’s first visit to his apartment. Powell develops a recurring ‘sound-track appoggiatura’ wherein, as the audience’s gaze lingers on the cake, a voice shouts “Cut!” And abruptly transitions into the next scene in the film studio. As William Johnson notes, “This sound-track appoggiatura suddenly identifies the fictional director with the person who is shaping the real film,” (Johnson).

Another example of Powell’s subversive style can be seen in the scene where Mark shows his films to his colleague, Vivian (Moira Sheerer). Through the use of intercutting, Powell juxtaposes Mark’s footage of his victims’ deaths with Vivian’s reactions, implicating the audience in her horror and disgust. The use of close-ups and slow-motion techniques further intensifies the emotions onscreen, creating a sense of discomfort and unease in the audience. By implicating the audience in Vivian’s reactions, Powell challenges them to confront their own involvement in the events of the film. Moreover, by creating a sense of complicity and self-reflexivity in the audience, Powell challenged viewers to confront their own morality and involvement in the events onscreen (Stein).

The entirety of Peeping Tom is filled with metaphors, illusions, ironies, and revelations that manifest through articulately placed symbolism or intentional manipulation of the mise-en- scene. As William Johnson states, “Reduced to verbal description, these networks of symbolism and allusion may already seem too heavy a burden for even the most compelling story- line to bear-and there are more to come. But on the screen they do not stand out baldly, one after another, like appendages to the storyline; instead, they are embedded in the whole fabric of the film” (Johnson). For instance, the use of mirrors represents the duality in the protagonist’s personality. Another metaphor is observed when Tom raises the tripod leg, which distinctly resembles an erect penis, lending to the sexual nature of the murders. The audience has to complete the metaphor in their mind, thus forcing them to engage with the sexual nature of the content (Johnson).

In Peeping Tom, the theme of “sight” is central, as voyeurism is inherently linked to the act of watching. Powell uses recurring close-ups of eyes to emphasize this theme and create a sense of unease in the audience. Furthermore, the film’s irony is highlighted by the fact that Helen’s mother, a blind woman, is the only character who can “see” Mark’s true nature. This contrast between vision and blindness serves to further emphasize the film’s themes of voyeurism and the hidden nature of human behavior. Through this use of visual motifs, Powell implicates the audience in the film’s themes, making them question their own relationship with the act of watching and the role of perception in shaping their understanding of the world around them. The film’s final scene is a poignant example of Powell’s use of lighting to symbolize power dynamics and character perspectives. Mark faces his back to Helen as he speaks to her, emphasizing their opposing positions. Powell’s lighting choices, which contrast light and dark, symbolize Helen’s angelic purity and Mark’s villainous nature. Moreover, these choices further symbolize the choices that Mark is faced with, as he must decide between giving into his dark impulses or finding redemption.

In addition to metaphors and symbolism, the film draws an analogy between scopophilia and cinema, implicating anyone who views the film. This analogy creates a distinction between the observer and the observed, placing the audience in the position of the former. The use of subjective camera techniques places the audience in the position of the voyeur, creating a sense of complicity between the audience and the protagonist, and making them question their own morality and involvement in the events onscreen (Stein). By positioning the audience as the observer rather than the observed, the film creates a sense of detachment from the events on screen and allows the audience to participate in the voyeuristic act without fear of repercussion, inherently creating a sense of moral conflict (Johnson).

Furthermore, the use of subjective camera techniques serves to place the audience in the position of the voyeur. This technique creates a sense of complicity between the audience and the protagonist, Mark, as they are made to experience the events of the film through his perspective (Johnson). By doing so, the audience is forced to confront their own morality and involvement in the events on screen, and question their own relationship with the act of watching. This complicity is further emphasized by the film’s use of close-ups and point-of-view shots, which allow the audience to see the world through Mark’s eyes and experience his perverse pleasure in watching his victims. Furthermore, the film’s title, Peeping Tom, predisposes the audience to expect violent and sexual content, particularly since the film’s target audience is primarily teenagers and young adults. The audience can empathize with the theme of guiltily watching something they are not supposed to. Powell uses this against them by using their psychological vulnerabilities and desires against them, leaving them feeling disturbed and questioning their own morality.

The theme of morality is a central concern when examining another factor for the criticism of Peeping Tom, which was Powell’s own involvement in the film. Audiences were horrified to learn that Powell had cast his own son to play young Mark, while he himself played the sadistic father (Stein). This revelation added another layer of discomfort to an already disturbing film, further complicating the audience’s relationship with the material (Johnson). Moreover, this also brings into question the filmmaker’s intention—in Powell’s case, being the commerciality. As Johnson notes “To the British critics of 1960, jolted by the film’s subject matter and the sense of complicity with Mark which it created, the commercial expertise of Peeping Tom must have seemed the last im- moral straw” (Johnson). Powell’s commercial intentions are reflected in his use of cinematic techniques such as irony and humor to entertain the audience, but this comes at the expense of dehumanizing Mark’s victims. The scene on set where Vivian’s body is comically discovered in the blue trunk during a rehearsal is a prime example of this. Although the humor may initially be amusing, it ultimately creates an eerie and uncomfortable atmosphere that was not well-received by many viewers. Furthermore, the protagonist, Mark Lewis, lacks any moral redeeming qualities, which further contributes to the unsettling nature of the film. Throughout the movie, Mark is shown as a disturbed and perverse individual who derives pleasure from watching and capturing his victims on film. He shows no remorse for his actions and even continues his behavior after being caught (Mulvey). This lack of moral redemption for the protagonist is significant because it challenges the traditional narrative structure of many films, where the hero or protagonist is typically portrayed as a morally upstanding character who faces and overcomes obstacles to achieve a positive outcome (Johnson). In Peeping Tom, however, the protagonist is not a hero but rather an antihero, and his actions are not justified or excused in any way. This forces the audience to grapple with uncomfortable and challenging questions about the nature of evil and the human capacity for cruelty.

In conclusion, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom utilizes a range of cinematic techniques to depict the thematic elements of voyeurism, morality, and the concealed aspects of human behavior. The film’s controversial reception during its initial release indicates the discomfort it evokes in viewers, as well as its enduring influence on the horror genre and the film industry as a whole. As examined throughout this essay, the negative response was attributed to various factors such as the prevailing social attitudes at the time and Powell’s personal involvement, among others. Nonetheless, the film’s deliberate artistic intentions that employ metaphor and cinematic techniques are essential to its ability to engage and affect audiences. Through the use of techniques such as irony, humor, and subjective camera work, Powell implicates the audience in the film’s narrative and challenges them to surpass the conventional boundaries established between viewer and film. This compels the audience to empathize with the protagonist while also developing a sense of unease and disgust towards his actions. Despite the initial criticism, Peeping Tom endures as a seminal work of British horror and an influential example of how films can challenge and subvert audience expectations while also providing commentary on the world around us.

Works Cited

Canby, Vincent. “Film: Michael Powell’s ‘Peeping Tom’:the Cast.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Oct. 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/14/archives/film-michael-powells-peeping- tomthe-cast.html?searchResultPosition=1.

Johnson, William. ‘Peeping Tom’: A Second Look – JSTOR. 1980, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1212185.

Meenan, Devin. “The Peeping Tom Controversy Explained: How Martin Scorsese Helped Save a Forgotten Gem.” /Film, /Film, 11 Sept. 2022, https://www.slashfilm.com/994834/the-peeping-tom-controversy-explained-how- martin-scorsese-helped-save-a-forgotten-gem/.

Mulvey, Laura. “Peeping Tom.” The Criterion Collection, 15 Nov. 1999, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/65-peeping-tom.

“Peeping Tom May Have Been Nasty but It Didn’t Deserve Critics’ Cold Shoulder.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 13 Nov. 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/nov/13/peeping-tom-john-patterson.

“Peeping Tom: No 10 Best Horror Film of All Time.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 22 Oct. 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/oct/22/peeping-tom- horror-powell?CMP=gu_com.

“Psycho vs Peeping Tom: Why Was Hitchcock’s Twisted Murderer Not a Career Killer?” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 4 May 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/psycho-peeping-

tom-alfred-hitchcock-michael-powell-horror-voyeurism-norman-bates- a9488026.html.

“Psycho.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Psycho-film-1960.

Sky. “The Moors Murders: Who Were the Victims of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley?” Sky News, Sky, 30 Sept. 2022, https://news.sky.com/story/the-moors-murders-the- victims-of-ian-brady-and-myra-hindley-10879310.

Stein, Elliot. “’A Very Tender Film, a Very Nice One’: Michael Powells ‘Peeping Tom’.” A Very Tender Film, a Very Nice One, 1979, http://www.powell- pressburger.org/Reviews/60_PT/AVeryTenderFilm.html.

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.