My dad’s library was always an intriguing structure to me. Covered in rusted papers and old ink, everytime I’d go there I’d feel a whirlwind of emotions at this towering mass of books that was so expansive and full of knowledge compared to little old me. When I was about 12, having moved on from the Percy Jacksons and Roald Dahls, I asked my father if I could read one of the oldest books in our library—a rustic old copy of The Kite Runner. Reluctant, he hesitantly tried to explain to me that it was beyond what I could handle at the time. As a defiant little reader, priding myself on acting older than I was and pretending to handle more than I could, I tried to plead my case and insisted that I could handle it. He promised that I could when I was about 15, but at that age, time seemed to move extra slow and 15 seemed decades away. Unable to concede with my insatiable curiosity, I would pretend to sleep and sneak into the library after everyone had gone to bed, spending my nights huddling over this book that had so consumed my thoughts.

I soon after learnt why my dad had been so reluctant to let me read the book, being the most insistent advocate for my addictive reading habit. In fact, upon getting through half way through the book, I found myself unable to hold back my composure. My friends were confused as to what had got me so heavily nauseated for over a week, and that a simple book could have that effect on a child. Till date, I don’t regret it, and it is one of the most powerful pieces of writing I was introduced to—albeit at an age slightly too juvenile.

I must attribute my love for historical fiction to Khaled Hosseini, who so tenderly threaded my consciousness into thinking about upbringings and lives other than mine. It was the first time I had read something so rooted in reality, where the villains weren’t all consuming forces like the God Ares, or evil masterminds like those of Skulduggery Pleasant. The villains of Khaled Hosseini’s books were tendencies that existed within every one of us—fear, corruption, institutional injustice—and his stories were rooted in truth. Though initially confused at the mechanics of child sexual assault and sodomisation (having had no idea that such evil even exist), I knew that there existed a real Hassan and a real Amir out there.

It was also the first time I had read a book where my characters grow up (and not within the span of 5 novels). Hosseini’s characters aged, and so did Afghanistan’s rich history. A child with imagination is able to accurately conceive of an Afghanistan with a sky filled with kites, stripped of its creativity and its love. A child with imagination, however, is not able to reconcile with the pain that comes with knowing of its reality.

I decided that I would use my love for literature as an initiation into my passion for history, reading narratives inspired by real people, rather than solely those of imaginative worlds. I have found that this cultivated my understanding of history and my empathy towards real people in a way that no consequent academic education has.

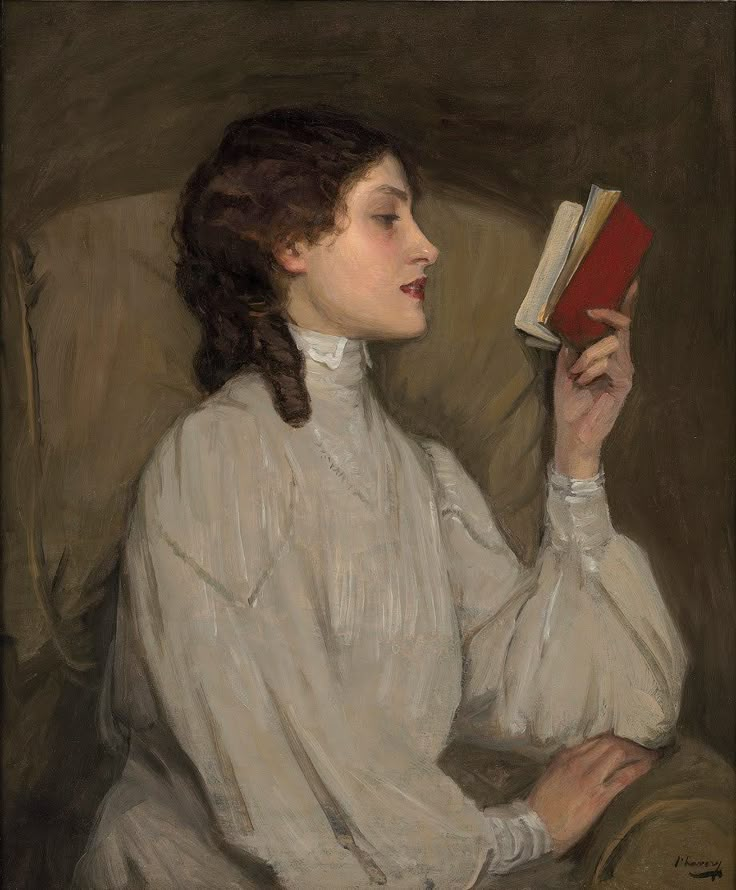

The beauty of fiction lies in its ability to engulf you into a narrative. First person narration, specifically, allows you to embody a character’s true experience, not as a friend or a historicist but truly transcendental in the sense that you are one with them. Simultaneously, it leaves room to fill in gaps with your own tenderness, allowing for true experience and empathy. The colour I imagine to be Afghanistan’s skies may not be the colour it actually is, and my friend may imagine a completely different colour as well, but just in having pictured it, we’ve made it our own. We’ve experienced the loss of freedom in Afghanistan ourselves. Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief allowed me to travel through time into entirely different worlds and truly understand the lived experience of people. I have personally felt Antoinette’s confinement, Sethe’s anxiety (if what she felt can be limited to a term as flippant as that), and Liesel’s thrill at discovering new books.

Presently, I’ve been reading a phenomenal novel by Syrian author Zoulfa Katouh, As Long As The Lemon Trees Grow. In the contemporary contect, this novel feels particularly urgent. Katouh refuses the distance of abstraction and insists on the lived, human experience of an ongoing history. It reminds us that stories of war, displacement, and survival are not sealed in the past but unfolding in real time, shaped by voices that are too often marginalized or silenced.

While history books often present timelines, political shifts, and economic structures, historical fiction reaches towards the interiority of the self. Through carefully imagined lives anchored in real contexts, readers can walk through the streets of Baghdad, Soviet Gulags, and through entirely different centuries, with all the fear, hope, longing, and resilience that history’s margins often fail to record. Dialogue becomes a powerful tool, allowing historical figures or fictional stand-ins to speak in voices that textbooks rarely attempt to recreate.

Symbolism and sensory description evoke the sound of rustling silk in a Victorian drawing room, the acrid scent of gunpowder on a battlefield, or the quiet dread in a colonized town. More importantly, historical fiction is the only way to truly know the lives of women, children, laborers, enslaved peoples, or minority communities whose stories were never formally documented. It teaches critical thinking as well; I’ve learnt to question who writes history, what is remembered, and more importantly, what is deliberately forgotten. I truly believe that curricula should incorporate historical fiction as an integral source of knowledge, teaching how history felt and personally carried forward into the present.

Kyra is an aspiring writer, artist, and philosopher. Her creative endeavours have been inspired by an interest in phenomenology, surrealist aesthetics, and unconventional gothic storytelling, deeply reminiscent of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche.